It’s old news that Brazil is enacting social quotas – both socioeconomic and racial – for public higher education. In my earlier post, I detailed the impact this sort of policy could have on the quality of higher education. However, before I had the chance to write a follow-up to that post, a new piece of legislation began being drafted to introduce affirmative action to the civil service.

This is not the first policy of its kind in Brazil. Yet, it is too soon to discuss the implications and effects of this law. Regardless of the final shape the bill takes, any affirmative action will have to grapple with the basic issue of identification of the beneficiaries.

In Brazil, racial classification has always been a contentious topic. For many decades, the government refused to even collect racial information, arguing that race was not a salient issue on this side of the Americas. However, even if one agrees that there is racial discrimination in Brazil, and that part of the country’s huge inequality hinges upon race and not only class and education, the issue of racial classification is not something to be quickly dismissed. A recent New York Times forum, for instance, shows very different perspectives.

On the one hand, Peter Fry, a leading anthropologist, argues: “[…], unlike the U.S., the majority of Brazilians do not classify themselves neatly into blacks and whites. In Brazil, therefore, eligibility for racial quotas is always a problem.”

On the other hand, Antonio Sergio Guimarães, a leading sociologist fights back:

Perhaps the biggest challenge in Brazil is the temptation to introduce a systematic verification of self-declared color or race to prevent fraud in affirmative action programs. Race and color are social constructs. It is impossible to define their borders scientifically. Passing is something inherent to this kind of classification. It can be motivated by selfish economic protection or by political altruistic reasons. The fear of fraud must be restrained to give a chance to these programs to flourish.

Ultimately, these scholars seem to be discussing an empirical and methodological issue of racial classification with wide implications for redistribution. Despite the known complexities of racial classification, much analysis relies on a single self-classification based on fixed, mutually exclusive, choices.

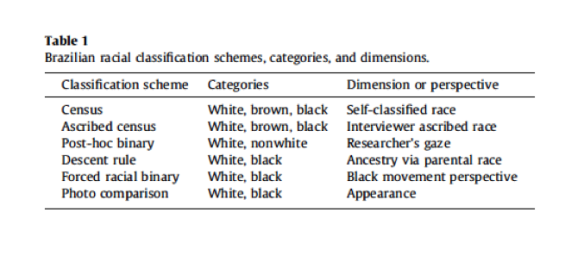

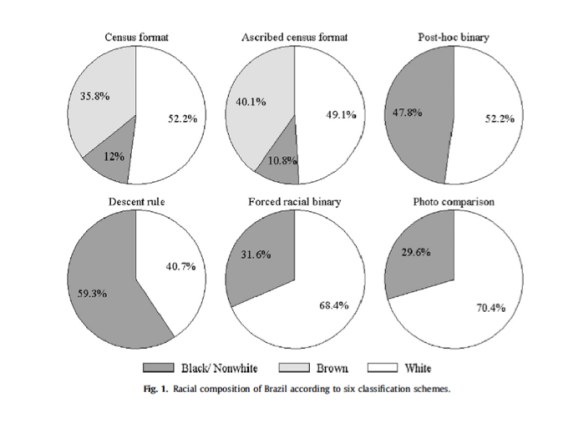

Bailey, Loveman and Muniz (2012) present an interesting analysis of Brazil’s racial make-up and racial inequality, taking different racial classification schemes into consideration:

They demonstrate that very different pictures of Brazil’s racial make-up are created depending on which scheme is followed. Comparing the most extreme cases, Brazil could be either 70.4% or 40.7% White. Beneficiaries of affirmative action could either comprise 29.6% or 59.3% of the population. These are hugely different percentages.

Furthermore, these different measurements are not necessarily robust. Even if more than one measure is used, there is still a lot of incongruence.

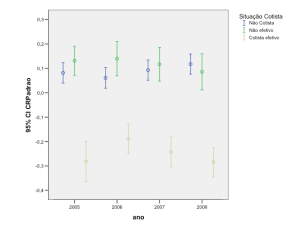

In their paper, they go on to convincingly show that different measures also imply different mappings of income inequality between those groups. Their findings do not necessarily challenge the finding that Blacks are, on average, worse off than Whites, but they do bring more precise, rigorous, and contextual evidence to support that claim. In any case, these findings do not mean that race should be disregarded and that it does not influence social interactions in Brazil. They argue that these different measures provide more evidence that race is a multi-dimensional social construct and should be analyzed as such – there is no “true race” to be measured.

But, what do these findings tell us when discussing redistributive policies based on race? Do these inconsistencies hinder any systematic implementation of affirmative action? Or are inconsistencies (and, to some extent, fraud) a “lesser-evil”, with affirmative action a good idea despite these issues? The recent policies seem to have embraced affirmative action despite these problematic measurement issues. The consequences of these choices are still to be fully understood.