(Ed.: The following is a guest post by Rory Truex, Ph.D. Candidate in Political Science at Yale University. Rory is currently conducting field work in China.)

Among China watchers, there is an ever-louder group of voices singing the imminent downfall of the country’s political system. The chorus goes something as follows: “The faux representation afforded by the National People’s Congress, the empty channels for public participation, the meaningless village elections— these shell institutions do little to stem the CCP’s growing legitimacy deficit. Protests are already on the rise. Sooner or later, something will happen and the people will rise up and demand real democracy. It’s only a matter of time.”

For many in the prediction game, that time has already come and gone, or it is rapidly approaching. In 2001, Gordon Chang predicted The Coming Collapse of China, asserting that underperforming loans would break China’s financial system and trigger the fall of the CCP within a decade. In a 2011 editorial, Chang revised his estimates to say that the system would fall within one year’s time. This has also proven false. In 1996, Henry Rowen used economic data to predict that China will become democratic “around the year 2015.”

Perhaps the reason the “fall of China” prediction has fallen flat to date is that it rests on the notion that Chinese citizens actually want a new political system. A simple glance at the data, or simple discussions with a few citizens, would make us reconsider this assumption.

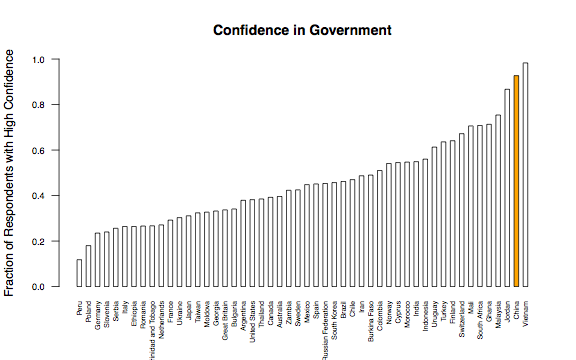

The figure above shows summary data from the fourth wave (2005-2008) of the World Values Survey (WVS). Among other attitudinal questions, the WVS asks respondents their level of confidence in their government on a four-point scale. The bars reflect the fraction of respondents responding “a great deal” or “quite a lot.” With the exception of Vietnam, Chinese citizens voice greater support of their government than any other country in the world.

Of course, we should take this fact with an oversized grain of salt. Cross-national surveys of this sort are notoriously bad and suffer from a host of biases— incomparable sampling procedures, poor translations, different cultural interpretations of question wordings, among others. Most importantly, respondents living in repressive political contexts— like China and Vietnam, for example— may be unwilling to voice their true opinions when asked sensitive questions about government. It may be that Chinese citizens have confidence in the CCP, or it may be that fear leads them to systematically bias their answers.

At the risk of sounding like a party mouthpiece, my guess is that the truth is probably closer to the former than we would like to believe. China scholars have long documented that Chinese citizens have a deep reservoir of trust in “the Center.” Many ostensibly subversive activities— protests, non-compliance with rules, petitions— are actually ways for citizens to communicate their grievances to the central government, which is perceived as responsive. The “fall of China” crowd likes to point to rising protest figures as evidence of a desire for change, but the vast majority of protests have nothing to do with political reform. Peter Lorentzen has argued that the regime deliberately allows this “regularized rioting” to help monitor lower level cadres.

In the end, public opinion in authoritarian contexts is difficult to gauge, and so we are left trying to blend imperfect survey data with more impressionistic anecdotal evidence. To build my own impressions, I have taken to asking a simple, direct question among my closer Chinese friends.

If you could change China’s political system today, what would you do?

There is no shortage of demands— more transparency, more freedom of speech, an open media, unregulated internet— but I’m always struck by how often multi-party competition is missing from the list. When probed on this issue, most will give a reply of the sort “this is not appropriate for China.” Some will flip the conversation back at me and point to recent Congressional debacles over the debt ceiling and fiscal cliff. These events are smugly broadcasted by China’s state media outlets, and they undermine the very credibility of the American system. If this is what democracy is, we’ll stick with our one-party system, thank you very much.

So does China want change? It is impossible to know for sure, but there seems to be a societal current pushing for limited liberalizing political reforms. Full-blown multi-party democracy and the “coming collapse” of the CCP?

I’m not sure we should be singing that chorus just yet.