- Joshua Foust delves into the Bradley Manning court-martial and reveals some fascinating insight into the proceedings, Wikileaks, and the man on trial. Foust’s final, depressing conclusion: “It says something about the world that such a tiny organization can create such disruption yet face so few consequences. In its wake, Wikileaks has left a trail of upended lives — including Bradley Manning’s. It will be sad to see such a troubled, fascinating young man be thrown into prison at the age of twenty-five, but that is the bed he made. It is approaching time for him to lie in it.”

- Seyla Benhabib on Erdogan’s culture war against Turkish secularism and the growing illiberalism of Turkish democracy: “This moral micromanagement of people’s private lives comes amid an increasingly strident government assault on political and civil liberties. Turkey’s record on journalistic and artistic freedoms is abysmal; rights of assembly and protest are also increasingly restricted.”

- Pakistan analyst Imtiaz Gul speaks of the difficulties ahead for Pakistan’s newly elected Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, including normalizing relations with the U.S.

- Women, family and academia: not an easy combination. “Our most important finding has been that family negatively affects women’s, but not men’s, early academic careers. Furthermore, academic women who advance through the faculty ranks have historically paid a considerable price for doing so, in the form of much lower rates of family formation, fertility, and higher rates of family dissolution. For men, however, the pattern has been either neutral or even net-positive.”

- The season of inspiring commencement speeches is upon us. Ben Bernanke at Princeton.

Category Archives: Elections

Wanted: A Few Good Experts on African ‘Chaos’

Experts on North and West Africa are hard to find. When Laurent Gbagbo and Alassane Ouattara of Cote d’Ivoire squared off over the presidency in 2011, for example, the coverage of the conflict was found lacking. Previously in 2005 there was a coup in Mauritania, and I remember being at my old job at the Council on Foreign Relations, scrambling to find a Mauritania expert. Now that Mali has heated up, I did a quick Lexis-Nexis scan of a few bylines who have written recently on the uprising there. Virtually none of them has published a thing on Mali in the past few years, either because of out-to-lunch editors or because their expertise is a chameleon-like thing that gravitates toward conflict (A welcome exception is Mike McGovern, whose work on West Africa is exemplary). Stewart Patrick of the Council on Foreign Relations even singled out the Sahel as evidence that ungoverned territories do not brew terrorism. Consider this gem from 2010:

For years, observers warned that Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Chad were gravely at risk. And yet the extreme ideology of al-Qaeda has failed to resonate with the region’s population, most of whom practice a relatively moderate brand of Sufi Islam. Despite weak institutions, vast un-policed territories, and porous frontiers, the region has failed to emerge as “the next Afghanistan.”

Oops (In fairness, Patrick’s overall point is something I largely agree with – that we often overreact to ungoverned spaces). The trouble, as I see it, is that chaos tends to breed not just extremism but also bad commentary – Robert Kaplan’s The Coming Anarchy is 224 pages of evidence of this annoying trend. In the early 1990s Richard Holbrooke described the emerging chaos in Somalia as “Vietmalia.” In the 2000s, Niall Ferguson called the chaotic and increasingly symbiotic relationship between Beijing and Washington “Chimerica.” Now we are being told that Mali is descending into what The Economist has termed “Afrighanistan” (Et tu, Economist?)

Notice a pattern? The world’s most prized minds on geopolitics have reduced the world’s problems into poppy headline-friendly phrases that launched a thousand think-tank brownbags. To be sure, the world looks increasingly complex – um, Tourags are whom again? Assyrians are not the same thing as Syrians? – and so these handy phrases can help explain difficult policy conundrums to a lay audience. They also dovetail with a larger trend in our pop culture of slapping two words together – “Ginormous,” “frenemy,” etc. – which is not all that atypical in world history textbooks – after all, “Eurasia” is a real part of the globe.

The trend of slapping two countries’ names together and calling it a clever solution comes from several forces. First, the pressure-cooker environment among experts and authors to coin new phrases, to sell books, and to be invited on the speaking circuit. “Offshore Balancing Against China’s Emergent Regional Hegemony in the South China Sea” is a less sexy title and less likely to get you a TED invitation than calling the Obama administration’s “pivot” to Asia our “Japanamericapinestralia”. Our Americas policy increasingly resembles a case of “Cubexazuela” (our primary interests are Cuba, Mexico and Venezuela). Trans-Atlantic relations can best be defined as Frermanitain (the club of France, Germany and Great Britain). And our approach toward Africa resembles a “Malgerisomaliopiabokoharamakenyongod’ivoire.” (I know it rolls off the tongue.)

Such neologisms are distracting and dumb down the debate of such areas of the world. Not only are they distortion of the reality on the ground, but they insult our intelligence by oversimplifying complex events. Which may explain why they are met with scorn generally from insiders (see “AfPak,” which was not only confusing but also probably should have been inverted), and even full-fledged rejection by the authors themselves (Ferguson even distanced himself a few years later from his “Chimerica” phrase and predicted an “amicable divorce” between China and America). The trend shows the utter lack of imagination among practitioners and academics in the field. There hasn’t been a good catchy “End of History” or “Clash of Civilizations” phrase to define our current era. So foreign policy wonks throw everything they can up against a wall and see what sticks. Hence, Afrighanistan.

I shutter to think what will happen the next time a civil war pops up in some forgotten corner of the globe. Expect more lazy comparisons to Afghanistan.

Representation by law? Gender quotas in Brazil’s elections

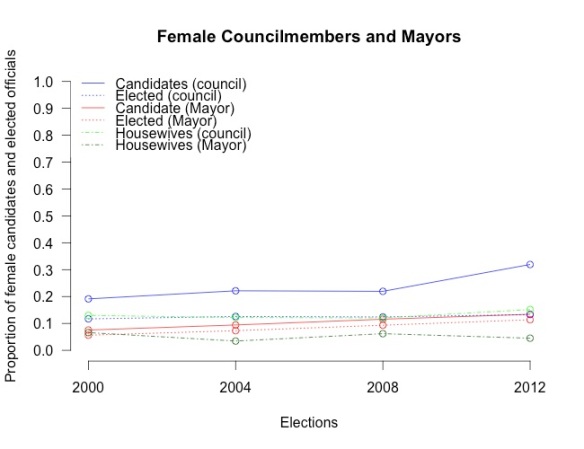

On January 1st, 2013, 7,646 women took office as members of the local legislatures in more than five thousand municipalities in Brazil. 665 women were also elected as mayors in these municipalities, marking the largest number of women to enter local office in Brazil’s history.

Is this latest achievement part of the trend started two years ago, when on January 1st, 2011, Dilma Rousseff took office as President of the country? After all, in 2010, not only did Brazil elect its first female president, Marina Silva also gained the largest vote share of any third-runner for the presidency since re-democratization in 1989. Or, are these numbers the direct effect of the gender quota law enacted in 2009? This law requires that a minimum of 30%, of women be on party lists for proportional elections (local, state, and federal legislators). This 2009 law, applied for the first time in the 2012 elections, made a similar 1997 gender quota law more effective by forcing parties to actually enlist women to their tickets.

Examining only the absolute number of elected women in Brazil can be misleading, however. Indeed, careful examination suggests that the proportion of elected women has only risen slightly despite the more effective enforcement of the quota law.

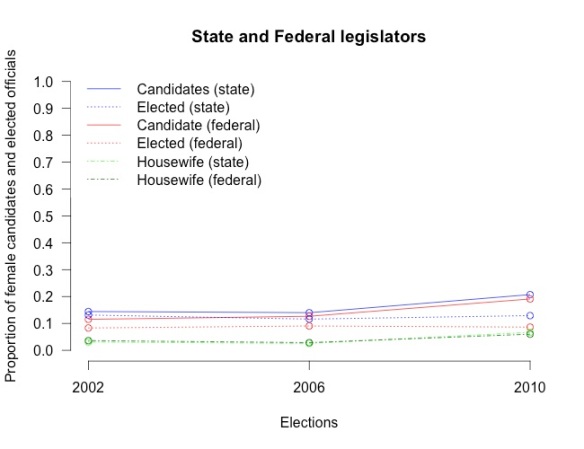

The graphs above tell us part of the story. We can see that the proportion of elected women still remains significantly less than elected men. The first graph indicates that even though the number of female candidates for local chambers has risen sharply (due to the enforcement of the quota law), the proportion of elected local female legislators is still very small. Similarly, the proportion of elected state and federal deputies is remarkably stable even through there has been a rise in the number of candidates in the 2010 elections, as shown in the second graph. Given that the gender quota does not affect majoritarian elections, it is a bit surprising that the proportion of elected female mayors has been rising more rapidly than the proportion of elected female local legislators.

One possible explanation for the under-performance of women in elections for local chambers is the lack of resources and support provided by the parties, which recruit women simply in order to formally reach the threshold demanded by the law. This is a difficult hypothesis to test but the graphs above shed some light on it. For instance, the number of female candidates who identified as “housewives” increased in the 2012 elections. This may reflect the greater influence the Electoral Justice had on parties to obey the gender quota law, leading parties to enroll female candidates who were related to existing male candidates.

The gender quota law provides a necessary first step towards equal gender representation. Nevertheless, making sure women have spots on party lists does not guarantee that they will have the resources or access to other factors necessary to get elected. Like other types of affirmative action, quotas tackle issues of inequality by guaranteeing access of underprivileged groups to the arenas in which they are systematically under-represented (these arenas could be the realm of elections, universities or jobs, among others). Yet, whether this type of affirmative action proves ultimately effective hinges upon empirical and normative assessments.

The Return of Israeli Moderation?

Not too long after the Israel-Hezbollah war, George Packer wrote an excellent profile of Israeli author David Grossman for the New Yorker. Grossman is an Israeli author who, along with several of his liberal cohort, has been engaged in a full-front assault on Israel’s hawkish foreign policy. Packer describes, in detail, how Grossman’s political opinions have evolved, like that of many Israelis, over the past few decades:

[At the time of the Yom Kippur War], his political views were conventional: Israel, surrounded by enemies, was destined to fight an eternal war, and the only imperative was survival. In 1967, the year of his bar mitzvah, Israel won the Six-Day War and occupied Gaza, the West Bank, the Sinai Peninsula, and the Golan Heights. In “The Yellow Wind,” Grossman wrote of his generation, “The surging energy of our adolescent hormones was coupled with the intoxication gripping the entire country; the conquest, the confident penetration of the enemy’s land, his complete surrender, breaking the taboo of the border, imperiously striding through the narrow streets of cities until now forbidden.” At the beginning of the occupation, Jewish families used to drive through the West Bank and Gaza on weekends, on tours organized by transportation companies like the one where his father worked; they would buy Arab kaffiyehs for next to nothing and wear them triumphantly in the streets of Hebron and Jericho. The Palestinians were crushed, and the Israelis were seduced by what Grossman calls “the temptation of strength, the temptation of arbitrariness.” At thirteen, he felt unambivalent pleasure about Israeli power. As he grew older, though, he became troubled by it; when friends or Army comrades urged him to join an outing to the occupied territories, he refused, saying, “They hate us, they don’t want us there. I cannot be like a thorn in the flesh of someone else.”

Much time have passed since this profile and since Grossman began his campaign. For years, it seemed, to those of us on the outside, that such pleas for moderation fell on deaf ears. While the settlements issue is not resolved, it appears that the Israeli “consensus” on a hardline against Iran is far from unassailable. Israel’s policy is already shifting away from military action. In a recent editorial in the New York Times, Graham Allison and Shai Feldman argue that the change of policy comes as the result of internal divisions within Benjamin Netanyahu’s government, primarily between Netanyahu and Defense Minister Ehud Barak. Indeed, several prominent Israeli political figures, including President Shimon Peres, have spoken out against unilateral military action. Moreover, as Allison and Feldman point out, the Israeli military establishment has unified in its opposition to military strikes.

Several obstacles remain, however. Most pressing, perhaps, is the possibility of a re-emboldened Netanyahu emerging from the January elections. Possible permutations of center-left coalitions consistently poll lower than Netanyahu’s coalition. In the last elections, in 2009, Netanyahu was able to form a rightist coalition despite receiving the second-most seats in the Knesset, the Israeli legislature. The centrist Kadima party, which received the most votes in 2009, was unable to form a governing coalition. It is unclear whether they will be able to unify various other centrist parties in order to succeed at this task in January. Much hope rests with Ehud Olmert, the former embattled Kadima Prime Minister. However, as Judy Rudoren argues in a Times op-ed, he faces many complicated challenges–some political, some legal, some moral–in his attempt to become prime minister once again. The titular question then can only be answered by a cautiously optimistic “maybe.”

No matter the outcome, these developments emphasize the non-unitary nature of Israeli domestic politics and foreign policy. In many ways, this mirrors a critical analytical hurdle that the field of International Relations faced several decades ago. As a recent “state-of-the-field” review article in the Annual Review of Political Science by Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith argues, IR has more or less overcome this crutch. Scholars have made countless important contributions to our understanding of international politics by exploring domestic political developments explicitly.

Perhaps nowhere is this domestic turn in IR more clear than in John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt’s controversial work on the US Israel lobby. Moreover, this analysis more or less reflects the public view of US foreign policy-making, whether true or not. It is not clear why this understanding has not extended to Israeli politics, which continues to be black- boxed in public discourse. Whatever the result of the next few months’ debate and politicking in Israel, the critical lesson for the rest of us should be not to essentialize Israeli foreign policy positions based upon the hard line it has taken so far.

For more of his thoughts on developments in Israel, follow William on Twitter.

Election’s Outcome is Huge News for Georgian Democracy

By Daniel F. Wollrich

On October 1, Georgia held parliamentary elections that were sure to be a victory for President Mikheil Saakashvili’s United National Movement party. Except they weren’t. In fact, challenger Bidzina Ivanishvili’s Georgian Dream coalition—“a group of progressive opposition forces in the Republic of Georgia”—prevailed and will enjoy a parliamentary majority. Even before all the ballots had been counted, President Saakashvili gave his concession speech, overtly accepting the shift in governmental control. The symbolic power of the election and the results’ acceptance by the leadership, however, is far more important and indicates a strong Georgian embrace of democratic governance.

Georgia, a post-Soviet state located in the historically conflict-ridden Caucasus region south of Russia and north of the Middle East, has a short democratic history. With two centuries of explicit Russian dominance (save a few years following the violent collapse of the Russian Empire and during the early consolidation of the Soviet Union), Georgia only reestablished its independence in 1991. While not immediately embracing a democratic institutional framework like the Baltic States, Georgia under Eduard Shevardnadze—former Soviet minister of foreign affairs and Georgian head of state from 1992 to 2003—experienced a mild improvement over the Soviet regime. The country’s politics were marked by stuttering liberalization and weak, often merely symbolic, democratic institutions. Fraud and corruption continued to mar the country’s government, sparking the Rose Revolution following the fraudulent November 2003 parliamentary elections. Shevardnadze was cast out and the Saakashvili era began. This marked the shift to a truly post-Soviet Georgia, establishing enough democratic institutions to earn the title “democracy” from Western observers (even if not a “full democracy”).

Of course, Georgian democracy has been far from flawless. Saakashvili, elected president in 2004 and re-elected in 2008, had seen his popularity wane in the past few years. Accusations of authoritarian rule had sprouted, derived from the strong hand he has played in instituting changes to Georgia’s political landscape. Saakashvili’s most overtly disturbing move, at least internationally, was his attempt to remove his challenger, Ivanishvili, from the political scene by revoking his Georgian citizenship. A law was invoked—driven by Saakashvili—that forbids Georgians from maintaining multiple citizenships. Since Ivanishvili was also a citizen of Russia and France (he has since renounced his Russian citizenship), he was stripped of his status as a Georgian citizen. A constitutional amendment introduced in May, however, may pave the path for a non-Georgian citizen (under certain conditions) to become prime minister. The legal battle remains unresolved, and when—or whether—Ivanishvili can become prime minister is yet to be determined.

More recently, the scandal surrounding abuse in Georgia’s prison system has deeply tainted the carefully cultivated righteous image of Georgian leaders. The torture, taunting, and sexual assault of prisoners sparked angry demonstrations, resulting in the resignation of recently appointed minister of interior Bacho Akhalaia. Moreover, defense minister Dmitri Shashkin was minister of penitentiaries after 2008, indicating the depth—and height—of the scandal in the government. The Georgian regime was struck at its heart, immediately prior to elections, and the evident overstretch of high-level governmental power suggested that Georgian authorities might reveal themselves unwilling to play by rules of fairness and democracy, should they lose the popular vote.

Yet, a warmer light shined upon Georgia’s future this month. The election’s winner was the democratic process. When Saakashvili conceded in spite of expectations that his party would prevail, he showed by action what his words had claimed for years: his rule was for bringing democracy to the Georgian people. In 2008, Georgia held what the Organization for Co-operation and Security in Europe called the “first genuinely competitive post-independence presidential election,” and this year, the country enjoyed its first democratic change in power.

Predicting where this leads is difficult. One key challenge not yet discussed here concerns Georgian sovereignty over its entire claimed territory and relations with its northern neighbor, Russia. Throughout his rule, one of Saakashvili’s primary goals has been shoring up the country’s autonomy and establishing territorial integrity, noting that he inherited autonomous or semi-autonomous regions in the northwestern Abkhazia, the north-central South Ossetia, and the southwestern Ajaria. Although he quickly and successfully reintegrated Ajaria, stoking optimism for the remaining two breakaway regions, South Ossetia and Abkhazia would prove more resistant. These difficulties stemmed in large part from these regions’ mighty benefactor to the north. This territorial problem continues to haunt Tbilisi, with no apparent solution. It will disrupt Georgian efforts at reconciliation with Russia, regardless of Ivanishvili’s desire to warm relations, and it will obfuscate any paths to NATO membership and official alliance with the West.

Domestic problems also trouble Georgia’s immediate political future. Opposition rallies have continued beyond the election and threaten domestic tranquility and the peacefulness of the transition, in spite of Ivanishvili’s calls for their end. In addition, as discussed above, the question of Ivanishvili’s citizenship and whether he can even become prime minister presents a peculiar and unfortunate case of domestic institutional manipulation interfering with democratic system processes. Regardless of who assumes the role of prime minister, the probability of political wrangling and the possibility of stalemate between the Georgian Dream coalition in parliament and Saakashvili and the United National Movement in the presidency until next year loom threateningly.

Nevertheless, one cannot underestimate the power of commitment to an idea and especially, as in this case, democracy. Although Saakashvili and Georgia’s political future once seemed intimately intertwined, the president’s prompt and willing concession suggests that Georgia’s governing ideology is not Saakashvili-ism but rather democracy and the rule of the people. Going forward, numerous factors must be watched: Will the Georgian Dream be a dream of democratic consolidation? Will the press be open and liberated and will transparency infiltrate the government? How will the new government relate to the West, Russia, and its other immediate neighbors? Will the dilemma of South Ossetia and Abkhazia prove obstructionist to international integration and domestic stability? These and other questions illustrate the challenges before Georgia’s new government. But the peaceful, legitimately democratic change of power in Kutaisi bodes well. This election is indeed huge news for Georgia’s democratic endeavors.

News from 2011: You’re All Dead Now

This post comes courtesy of my always-brilliant colleague Louis Wasser’s unassailable devotion to the discipline. The following image comes from Louis’s Yale library copy of Samuel Huntington’s Political Order in Changing Societies, published by Yale University Press in 1968. This, of course, was also the year of Richard Nixon’s ascendency to the White House.

Underlined in the text is one of Huntington’s claims about political culture in a country like the United States:

Underlined in the text is one of Huntington’s claims about political culture in a country like the United States:

…the top national leadership and the national cabinet are comparatively free from corruption…the top leaders of the society remain true to the state norms of the political culture and accept political power and moral virtue as substitutes for economic gain (p. 68).

In response, an astute and self-aware Yale student, presumably mockingly, writes “Watergate forever.” What follows is a back-and-forth between Yale students about the impact of Watergate specifically and the Nixon Presidency more broadly.

The debate is headlined by the comment “News from 2011: You’re All Dead Now.” The irony is that neither the commentators nor their arguments are likely “dead” in any sense of the word. For instance, one student writes that “we had no choice–McGovern would have driven the country straight to hell. we had to vote for Nixon to prevent socialism…” Such logic is alive and well among many segments of the America electorate even today. Indeed, if we had any news to report to the past from 2012, it would be this reality–elections, even 40 years after Watergate, remain fertile ground for paranoid political half-truths.

For more of his not-so-optimistic thoughts about elections, follow William on Twitter.

The Junta and the Brothers

Egypt’s democratic future is bright! Except, of course, that it probably isn’t — at least in the near term. The process of ‘transitioning to democracy’ under the stewardship of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) has largely been a sham, a long con carried out by the junta as it has sought to preserve military power and privilege.

The end of last month brought a symbolic — albeit uninspiring — milestone in this process, with the armed forces making a show of formally transferring power to the recently-elected civilian president:

Egypt’s new President Mohamed Mursi said on [June 30] the military that took charge when Hosni Mubarak was overthrown last year had kept its promise to hand over power, speaking at a ceremony to mark the formal transfer of authority.

This ceremony capped a month of rapid political developments, against a backdrop of apparent confrontation between the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) and the generals, interspersed with conciliation. Highlights from June — which I was fortunate to be able to spend in Egypt — include swirling rumors about Mubarak (ismubarakdead.com); the invalidation of parliament; naked power grabbing by SCAF through a constitutional declaration; and the presidential run-off round, accompanied by Egypt’s collective holding of breath as the announcement of results was delayed.

Fun times with the Brothers and the junta have continued into July. Juan Cole noted last week:

Egyptian President Muhammad Morsi tried to steal third base on [July 8], announcing that he was calling back into session the dissolved Egyptian parliament. It would continue to meet, he said, until new parliamentary elections, to be held within 60 days of the completion of the new constitution. He thus took on both the Supreme Court and the officer corps, setting the stage for a face-off.

Apparently cute photo ops aren’t everything (check out the hyperlink embedded in the selection from Cole, above); the military and the oh-so-impartial judiciary wasted little time before hitting back, a New York Times article explained:

Egypt’s highest court and its most senior generals on Monday [July 9] dismissed President Mohamed Morsi’s order to restore the dissolved Parliament as an affront to the rule of law, escalating a raw contest for supremacy between the competing camps… [A]t its core, the fate of this Parliament is another chapter in the long-running battle between the Muslim Brotherhood and the military[.]

(For particulars of parliament being dissolved, see this Arabist post, including Tamir Moustafa’s comment at the bottom of the page.) The result? “Not so defiant: Egypt’s parliament meets for 5 minutes” — followed shortly after by Morsy seemingly backing down, at least for a moment. The matter is currently in the hands of an administrative court, and decisions on this and other critical issues are slated for today, July 19.

How Should Obama/Romney Respond to the Bad Jobs Report?

In light of Charles Decker’s great post on our blog about the Obama Presidency, I thought I would share a couple of great links I saw about the campaign, relating to the new jobs report, which, in case you hadn’t heard, was not great. Unemployment remains at 8.2% and, after adding 226,000 jobs per month in the first quarter, the economy added “only” 80,000 jobs in June.

To make matters worse for the Obama administration, history does not look favorably upon a President’s re-election prospects when the economy is poor. The woes of Jimmy Carter in 1980 and George H.W. Bush in 1992 are the most recent but not the only examples. However, the news may not be all that bad for Barack Obama.

At the great New York Times election blog, FiveThirtyEight, Nate Silver has put together a new economic index as part of his model to predict the electoral fortunes of potential incumbent candidates. While the model is incomplete and worth keeping an eye on moving forward, his preliminary findings merit a mention in light of the jobs report:

In general, values of the index below 2.0 point to cases where the incumbent president will actually have become the underdog. The economy was quite terrible by the point in 2008 and getting worse, and it was a complete disaster in 1980. Meanwhile, in 1992 when Mr. Bush lost, the economy would have looked quite poor to voters based on real-time data. With the economic index now at 2.5 percent, Mr. Obama is just above this break-even point, but not by much.

Moreover, it’s not quite clear that Mitt Romney’s campaign will be able to focus this election on jobs and unemployment. Even if the campaign now has its primary message on track, it may not receive the support it needs from the Republican Party. At TPM, Brian Beutler does a nice job discussing the Romney campaign’s inability to overcome its party’s tendency to bring non-economic issues to the forefront, often encouraged by the Obama campaign, of course:

It seems to me that every time something other than the economy dominates the headlines, the Romney camp, smartly, tries to steer the conversation back to the economy. It’s his best hope for the election. That was a particularly urgent imperative last week, when the Court ruling was the news, they’d just handed Obama a key victory, and uncomfortable comparisons to Romneycare were only a followup story away. Solution? Wave it off, pledge allegiance to the dissenters, talk about the economy again.

But instead GOP leaders in Washington wanted to turn the story around on Obama and Washington Democrats. They saw a shiny object chased after it, and ran roughshod over Romney along the way.

This seems to happen over and over again. The Obama campaign has been deft at keeping other major stories in the news — from student loans to women’s rights to tax equity to immigration and on and on. It’s all perfect bait for movement conservatives and House and Senate members, and each time they take it you can practically hear the cries of frustration from Boston. Inevitably Republicans find themselves talking about something other than the economy, and forcing the party to re-air all of the primary-season crazy they hope voters never see.

Obamaland: The Obama Presidency in Political Time

From now until November 6th, Barack Obama will be fighting for his political life. Mitt Romney still isn’t inspiring any Shepard Fairey “HOPE” posters, so Obama’s challenge will be to rally and inspire a base that is skeptical about his achievements and unsure of his intentions. Most of all, Obama will have to overcome a pervasive sense of disappointment bordering on betrayal that, after Hope and Change, we’re stuck with politics as usual. However, if we look at Obama’s presidency from a historical perspective, we begin to see that in some important ways the game was “rigged” against him from the start. The problem goes beyond an obstructionist Congress and a hostile and activist Supreme Court to the very heart of what we mean by “American politics.” We must situate Obama’s administration in its proper historical and ideological context.

The days and weeks surrounding Barack Obama’s election in 2008 were so exciting, the political environment so kinetic, that an honest-to-goodness political science topic received considered deliberation in the media. Even weeks before Obama’s election, pundits declared presidential blowouts extinct. Once Obama ran up the score on McCain, however, the same pundits debated whether 2008 was a realigning election. Several landmark works in American politics from the 1950s through the 1970s proposed that a special few elections were political realignments. (For a masterful lit review and critique, see David Mayhew, Electoral Realignments: A Critique of an American Genre.) Although authors have different definitions, some key claims about realignment remain constant: these elections are rare (1860, 1896, and 1932 are usually held as the examples); they create a sharp and durable shift in voter allegiance; voter engagement and turnout are unusually high; and major policy changes come about as a result of the election.

While 2008 was a triumph for Obama the candidate and a stinging rebuke of the Bush administration, it failed to meet most of these criteria for realignment. Turnout was up, but it was not accompanied by a higher level of serious political engagement. (Witness the failed transition of Obama for America from a campaign to an administration organization.) Furthermore, Obama’s victory was more about a mood or a feeling than any particular policy vision or set of proposals. This is a perfectly fine way to win an election, especially with a candidate as skilled and inspiring as Obama, but it does signify “politics as usual,” not any durable shift in government.

Eight Observations from the Greek Election (Part 2)

The Euro Strikes Back!

I devoted the first part of this post (the first four observations) to a discussion of the election results. In this second part, I explore the consequences of the electoral results. The immediate outcome was, of course, the formation of a pro-Euro coalition government between plurality winning center-right New Democracy and two center-left parties, Pasok and the Democratic Left. But what will this mean for Greece, Europe, and the global economy moving forward? On the eve of Antonis Samaras officially taking the reigns as Prime Minister and the “Troika” (the International Monetary Fund, European Central Bank, and the European Union) visiting Greece to assess its financial progress, I thought it would be appropriate to take a second post-election pulse of the nation.

5.) Greeks accept the euro but reject the terms of the bailout

Despite the electoral defeat of Alexis Tsipras’s anti-bailout Syriza party, the pervasiveness of anti-bailout sentiment in Greece is manifest. Over half the votes from the June 17th elections went to parties opposed wholesale to the terms of the 130 billion euro bailout. Greek and European leaders took notice. Although medical ailments prevented him from personally attending the EU summit in Brussels last week, new Greek Prime Minister Antonis Samaras sent a letter to European leaders asking for revised terms to the bailout. The letter was short on detail but contained guarantees that Greece would work hard at political reforms.

As the Troika descends upon Athens once again, it appears that the letter previewed a larger effort by the coalition government to negotiate more lenient terms. The current terms have made successive receipt of rescue funds contingent on Greece meeting a set of “fiscal targets” and enacting a series of austerity cuts, making this deal wildly unpopular in Greece. While the government still hopes to meet the fiscal targets set by the Troika, they are expected to ask for greater leeway in the means by which they will meet them. That is, less forced austerity. Seeing as the current “austerity for growth” program has the Greek economy contracting a projected 6.7% in 2012, the Greeks may have a point.

At first, it appeared that Germany Europe would remain steadfast in its refusal to alter the terms of the original bailout. However, pressure from Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy and Italian Prime Minister Mario Monti for a new approach to dealing with the Eurozone crisis has left Greek observers hopeful that some terms may be renegotiated. In the words of Deputy Finance Minister Christos Staikouras before meeting with the Troika,

The climate is becoming more favorable to changes and adjustments provided we meet our commitments and work towards implementing targets.

We will soon find out if he is right or not.

6.) International organizations affect domestic politics and domestic politics affect international organizations

In November 2011, then Prime Minister George Papandreou, of Pasok, proposed holding a public referendum on the newly renegotiated debt deal. As the June 17th elections showed, such a referendum would likely have failed. Sensing this outcome, European leaders summoned Papandreou to Cannes where he was “reproached” before an upcoming G-20 meeting. Papandreou returned to Athens and promptly cancelled the referendum. Within weeks, his government had collapsed. Within months, his party had been reduced to its lowest vote share in decades. The impact of EU leaders on the Greek polity seem shocking, even months later. Not only did these international actors “convince” Papandreou to change domestic policy but they also effectively ended his premiership.

The aftermath of the June 17th election have demonstrated that the causal arrow can run in the other direction as well. As detailed above, the success of anti-bailout parties like Syriza has forced the Samaras government and, by extension, the European Union to rethink their approach to the bailout deal. The results of the upcoming negotiations of the terms may even shape how the EU deals with future states asking for aid. Finally, as I discuss below, these electoral results may even lead to structural change in the European Union itself.

7.) The EU finally suffers from its democratic deficit

For decades, the European Union has suffered from what critics have called a “democratic deficit.” With a few exceptions, EU integration has progressed without the approval of domestic majorities. However, up until very recently, the problems with the democratic deficit have been primarily theoretical. To use a famous example, after the Dutch and French rejected the European Constitution, most of it was repackaged as the Treaty of Lisbon and approved in both countries.

This approach has more or less worked because the EU has provided member states with a plethora of tangible and intangible benefits without asking for much in return. Although states would lose national sovereignty, the loss was rarely so great that it would become objectionable to democratic majorities. Then came the euro.

The euro represented the greatest single sacrifice of national sovereignty in the history of the EU. However, it also held great promise, again, both in tangible and intangible ways, for the member states. In many ways, it reflected the “high risk, high reward” mindset endemic to the 1990s and early 2000s. Although domestic opposition was more pronounced, majorities either favored or began to favor the adoption of the euro, as they had with past measures of EU integration.

In 2012, however, the euro is in crisis. And, as these Greek elections show, support for the euro in individual member states is dropping. For Europeans, the only way to save the euro may be to proceed even further with EU integration. In this past week’s EU summit, European leaders agreed to permit the direct transfer of rescue funds to domestic banks from the ECB’s central bailout fund in exchange for direct supervision of the banks by the ECB. The deal essentially eliminates member state governments as the middlemen. Moreover, European leaders are discussing similar agreements that would establish debt pooling and Eurobonds (sold on the basis of German credit) in exchange for further central supervision of member state finances. In brief, European leaders have recognized that the only way to save the Eurozone, counter-intuitively, may be deeper fiscal integration.

However, European publics take erosion of national sovereignty quite seriously. In the past, they have been willing to accept it because of its gradual nature. However, the current Eurozone crisis requires swift action that may force European governments into deeper integration. While the anti-bailout parties were defeated in this election in Greece, a push for deeper integration with the EU by the Samaras government may spur a backlash that ultimately brings to power anti-EU parties. In this regard, Greece could be the harbinger for the idea that for the first time, the EU may finally suffer the consequences of its democratic deficit.

8.) The coalition government does not inspire confidence

The coalition government, meant at first to be a unity government of all major parties, is a coalition in name only. For all intents and purposes, it is a New Democracy government. Syriza refused to partake in the government altogether, preferring to be in opposition. New Democracy’s coalition partners, Pasok and the Democratic Left, refused to take cabinet positions. Syriza’s motivations are clear: they oppose the bailout wholesale and will not be minority partners in any coalition that accedes to the bailout terms. The motivations of the leftist coalition partners are less clear. It appears, however, that after failed negotiations for high cabinet positions, these parties are merely insulating themselves from the inevitable political damage that comes from enacting austerity protocols.

In an interview with the Guardian immediately following the elections, Dimitris Keridis, professor of political science at Panteion University in Athens said that

The secret to this government surviving will be trust among the three partners. If they fragment, the only beneficiary will be Syriza. It won’t be easy in a political culture that is, anyway, not used to coalitions and in a country that faces such tough decisions.

Almost on cue, the leftist parties refused cabinet positions and proceeded to distance themselves from the coalition government. While such behavior befits Syriza, an opposition party, it is befuddling from New Democracy’s coalition partners. Indeed, these developments do not bode well for the success of the coalition government. At any point, it seems, New Democracy could lose the parliamentary majority it possess thanks to the coalition. This will make tough political reforms very difficult to enact. New Democracy, fearing backlash, will be reticent to push for policies that would make it easy for their coalition partners to abandon them. Unfortunately, many of those policies might be the ones necessary to reform Greece and spur economic growth.

For more of his musings on politics, follow William on Twitter.