Whether it was democratization or WMDs, Iraq was the “pick a reason, love the policy” war. Conversely, drone strikes have become the “pick a reason, hate the policy” war. A consensus appears to be emerging against drone strikes. Even the Obama administration seems to share this assessment to some degree. But why? Drones are considered effective at weakening al-Qaeda networks not only within policy circles but also academia as well. In a recent working paper, Patrick Johnston and Anoop Sarbahi suggest that “by enabling both intelligence collection through overhead surveillance and direct targeting of suspected terrorists, drones reduce militant violence by increasing the costs of militant activities and creating an incentive for militants to lie low to avoid being targeted.” Christine Fair argues that not only are drones the best possible option to deal with militants in the tribal areas of Pakistan but that the degree to which they foster anti-Americanism may be exaggerated. President Barack Obama drove this point home in his speech at the National Defense University yesterday afternoon:

Our actions are effective. Don’t take my word for it. In the intelligence gathered at bin Laden’s compound, we found that he wrote, “We could lose the reserves to enemy’s air strikes. We cannot fight air strikes with explosives.” Other communications from al Qaeda operatives confirm this as well. Dozens of highly skilled al Qaeda commanders, trainers, bomb makers and operatives have been taken off the battlefield. Plots have been disrupted that would have targeted international aviation, U.S. transit systems, European cities and our troops in Afghanistan. Simply put, these strikes have saved lives.

However, Americans have still grown increasingly disenchanted with drones. I believe that this is due to five main reasons. As with support for the war in Iraq, not all Americans “hate” drones for the same reason or reasons. Ultimately, however, it appears that public opinion has begun to crystallize against drones due to some combination of the following reasons.

It’s a video game technology. The argument here is that drones are taking the humanity out of warfighting, which, in turn, makes policymakers more likely to use them. In conjunction, if you believe that drones make conflict and death more likely in the long run, it is easy to see why you would also worry about the implications of these new technological innovations. This is likely not a large driver of public opposition to drones for three reasons.

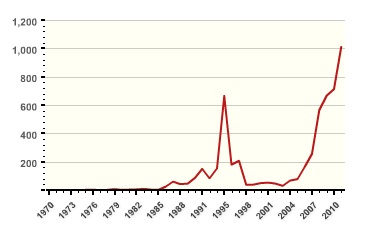

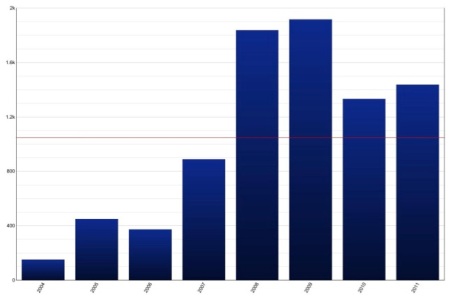

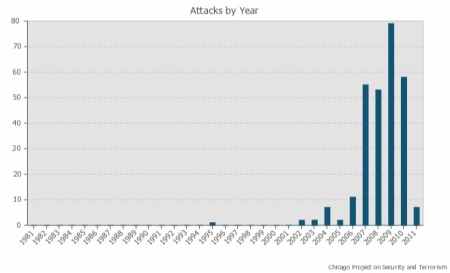

First, there is always a bit of shock and confusion when a new technology of war emerges but, ultimately, public opinion returns to equilibrium. I would hate to be a part of the generation that had to face the sudden emergence of air power, nuclear weapons, or tanks. Drones pale in comparison. Second, drones are actually not that new. The United States has been using drones since the First Gulf War and continued to do so throughout the 90s. Increased use notwithstanding, never before has there been such public outcry against drones. Third, it seems strange that the American public, which is notoriously casualty-averse, would be opposed to the use of weapons that minimizes American casualties. Indeed, military officials attribute the execution of Operation Allied Force in Kosovo without any combat deaths in part to the use of drones. President Obama emphasized this final point in his speech yesterday:

So it is false to assert that putting boots on the ground is less likely to result in civilian deaths or less likely to create enemies in the Muslim world. The results would be more U.S. deaths, more Black Hawks down, more confrontations with local populations, and an inevitable mission creep in support of such raids that could easily escalate into new wars.

It goes against international law. It is not clear to me that U.S. public cares all that much about international law, especially if ignoring it helps protect the homeland from terrorist attacks. Assuming that they do care, however, are drone strikes in accordance with international law? I am not a lawyer and do not wish to pretend that I am. Fortunately, our President is! He spoke directly about this concern yesterday:

America’s actions are legal. We were attacked on 9/11. Within a week, Congress overwhelmingly authorized the use of force. Under domestic law, and international law, the United States is at war with al Qaeda, the Taliban, and their associated forces. We are at war with an organization that right now would kill as many Americans as they could if we did not stop them first. So this is a just war — a war waged proportionally, in last resort, and in self-defense.

The United States appears to be on tenuous legal ground here. The entire claim rests on whether the U.S. can be at “war” with non-state actors. The entire premise of international law relies on mutual contracts between leaders of state actors. As such, the United States cannot technically be at war with a non-state actor and, as such, violates international law when it enters Pakistani territory without the permission of its leaders. A more plausible claim for legality, it seems, would be that the U.S. is actually acting with the permission, whether implicit or explicit, of Pakistani authorities. One would hope that increased transparency in the process would allow American officials to restate their claim for legality in these terms.

It is unconstitutional to target an American citizen without due process. As much as they do not care about international law, Americans certainly care about domestic law. Since I still remain not a lawyer, I will again lean on our President for a response:

I do not believe it would be constitutional for the government to target and kill any U.S. citizen — with a drone, or with a shotgun — without due process, nor should any President deploy armed drones over U.S. soil.

But when a U.S. citizen goes abroad to wage war against America and is actively plotting to kill U.S. citizens, and when neither the United States, nor our partners are in a position to capture him before he carries out a plot, his citizenship should no more serve as a shield than a sniper shooting down on an innocent crowd should be protected from a SWAT team.

At first blush, this is a persuasive argument. Ultimately, however, the President is relying on the same preventive action/imminent threat logic that President Bush used in favor of invading Iraq. Problematically, unlike the sniper, the hypothetical target of the drone strike has not committed a lethal crime yet. Moreover, even if he has, he would be entitled to due process rather than a public execution. In his response to the speech, Senator Rand Paul immediately picked up on this thread:

I’m glad the President finally acknowledged that American citizens deserve some form of due process. But I still have concerns over whether flash cards and PowerPoint presentations represent due process; my preference would be to try accused U.S. citizens for treason in a court of law.

I don’t agree with many (any?) of Paul’s other positions but he’s right on here and I doubt this objection goes away. if the administration is serious about curbing public opposition to drone strikes and due process, it must do better.

Too many civilian casualties. When it is said that the American public is casualty-averse, it is in reference to American casualties abroad. Deaths in Syria have reached nearly 100,000 but intervention in Syria, risking American lives, remains even less popular than drones. Civilian deaths in Iraq over the past decade have topped that. When publics are asked to weigh the costs and benefits of a national security abroad, they will tolerate a large number of non-American deaths in exchange for protection from a large number of American deaths. President Obama spoke about this tough choice at length yesterday:

[As] Commander-in-Chief, I must weigh these heartbreaking tragedies against the alternatives. To do nothing in the face of terrorist networks would invite far more civilian casualties – not just in our cities at home and our facilities abroad, but also in the very places like Sana’a and Kabul and Mogadishu where terrorists seek a foothold. Remember that the terrorists we are after target civilians, and the death toll from their acts of terrorism against Muslims dwarfs any estimate of civilian casualties from drone strikes. So doing nothing is not an option.

More conventional military options, while possibly as effective, are less precise and more destructive; they would only generate more collateral damage and American losses (remember this mess?). As long as the American public believes that military action abroad is needed to protect the homeland, drones will be the weapon of choice.

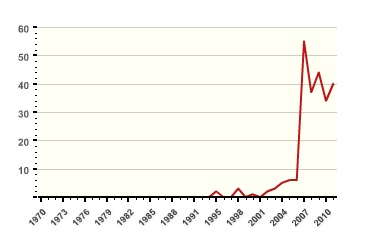

Drone strikes create more terrorists in the long run. As I suggested above, the evidence seems to indicate that drone strikes have been fairly effective at attacking militants hostile to U.S. interests in the short-term. What about in the long run? As the logic goes, drone strikes reduce militant numbers today but create more anti-American militants tomorrow. Given the rise in anti-Americanism since 9/11, the public is likely to be fairly receptive to this logic (even if they do not care what other countries think of the United States).

Whether this argument holds is unclear. A majority of Pakistani society opposes the drone strikes. However, as Fair and her co-authors suggest, we simply do not know what Pakistanis in the tribal areas, that cradle of terrorism, believe. Some evidence suggests that Pakistanis might support drones since there is little to no actual law enforcement in the area. It might also be the case that Pakistanis in these areas might simply not be aware of the origins or nature of the strikes on the militants. I am not expert on Pakistani (or Yemeni) society and, as such, do not want to make assumptions about something of which I know little. However, it does seems like using drones so heavily in Pakistan (and Yemen) commits exactly this type of error. Why continue a policy–and to such a large degree–the consequences of which are so poorly understood?

Concerns about the long-term implications of drones will remain as long as this uncertainty lingers. Policymakers have political and electoral incentives to make short-term policy decisions, with less consideration for the long-term implications of their policies. If public opposition rises in spite of the apparent short-term effectiveness due to the perceived dangers of continuing the policy in the long run, then it is likely that the majority of policymakers, including the President, will reverse course. Unless the happens, however, it seems unlikely that we will see an end to drones any time soon. If President Obama’s speech is any indication, it is far more likely that drones will be coupled with more active, non-military engagement abroad:

I believe, however, that the use of force must be seen as part of a larger discussion we need to have about a comprehensive counterterrorism strategy — because for all the focus on the use of force, force alone cannot make us safe. We cannot use force everywhere that a radical ideology takes root; and in the absence of a strategy that reduces the wellspring of extremism, a perpetual war — through drones or Special Forces or troop deployments — will prove self-defeating, and alter our country in troubling ways.

So the next element of our strategy involves addressing the underlying grievances and conflicts that feed extremism — from North Africa to South Asia. As we’ve learned this past decade, this is a vast and complex undertaking. We must be humble in our expectation that we can quickly resolve deep-rooted problems like poverty and sectarian hatred. Moreover, no two countries are alike, and some will undergo chaotic change before things get better. But our security and our values demand that we make the effort.

This means patiently supporting transitions to democracy in places like Egypt and Tunisia and Libya — because the peaceful realization of individual aspirations will serve as a rebuke to violent extremists. We must strengthen the opposition in Syria, while isolating extremist elements — because the end of a tyrant must not give way to the tyranny of terrorism. We are actively working to promote peace between Israelis and Palestinians — because it is right and because such a peace could help reshape attitudes in the region. And we must help countries modernize economies, upgrade education, and encourage entrepreneurship — because American leadership has always been elevated by our ability to connect with people’s hopes, and not simply their fears.

For more of his thoughts on drones, follow William on Twitter.